The quiet epidemic we do not name

Grief is a universal human experience, but how we process it is anything but universal. In Australia, where the national character leans hard into self-reliance, understatement, and dry humour, grief (particularly male grief) often slips by unnoticed. The classic image of the stoic Aussie bloke, silent in the face of tragedy, isn’t just a stereotype. It’s a social script.

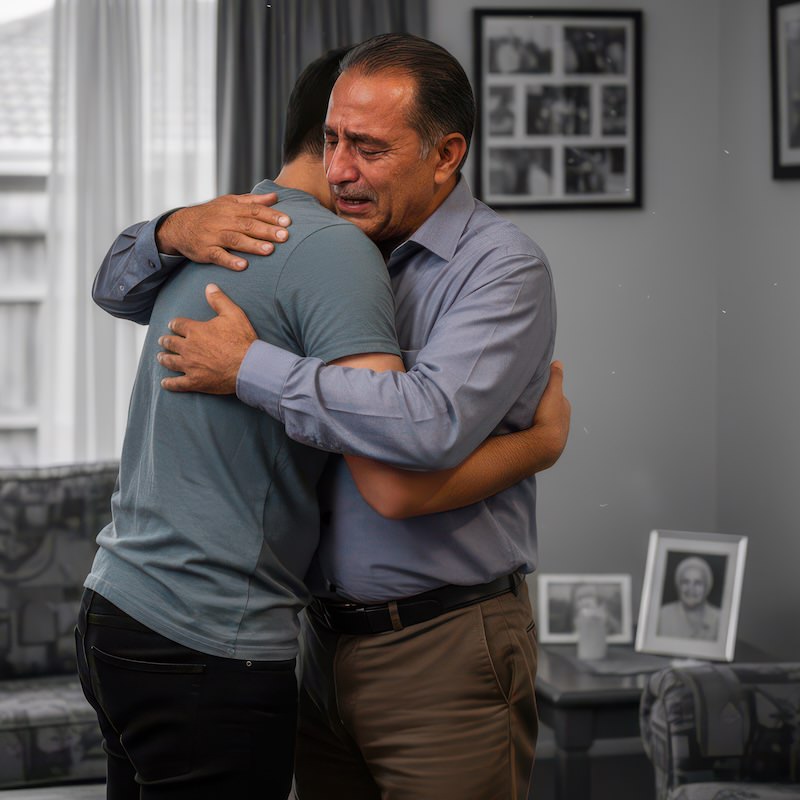

Men in midlife, especially, are expected to keep calm and carry on. If a parent dies, a mate dies by suicide, a marriage ends, or a child drifts away, we’re told, implicitly and explicitly, to bottle it up, stay strong, and get back to work. The tears can wait. The pain is private. And the timeline for expressing it, if at all, is measured in minutes, not months.

This script is doing real harm.

We now know that men are disproportionately affected by what Dr Megham Marcum, a US based psychologist, refers to as “compounded grief”, losses that accumulate without resolution. Divorce. Death. Redundancy. Regret. These are not isolated events, but often cluster during midlife, precisely when men are least equipped with language, support networks or social permission to respond meaningfully.

Rituals in ruins

Ritual is how societies metabolise emotion. It gives structure to chaos, form to formlessness, and rhythm to rupture. Every culture since the beginning of time has had some version of ritual to process grief. Chants, vigils, mourning clothes, periods of reflection, meals shared in silence or song.

But in contemporary, secular Australia, grief rituals have withered under the weight of efficiency and discomfort. Funerals have become shorter. Grieving periods are tighter. Black has been replaced by “smart casual.” We’ve moved from solemnity to slide shows, and from pathos to playlists.

This is not necessarily a mark of disrespect. Australians value informality and tend to resist overt displays of sentiment. But when rituals become shallow or optional, we rob ourselves of something fundamental: the chance to feel grief fully, share it communally, and recover in a structured way. Men, in particular, are ill-served by this erosion. With fewer natural outlets for emotion and less cultural permission to seek help, they risk becoming casualties of their own stoicism.

We don’t know what to say, so we don’t

Ask a group of middle-aged men how they’re doing after a loss, and you’ll often hear variations of: “I’m managing,” “It is what it is,” or “Can’t change it, mate.” The language of grief is muted, sometimes absent altogether.

While women are more likely to lean on friends, family, and professional help, men often choose silence. They may feel it’s unmanly to show vulnerability. Or worse, they fear becoming a burden. Cruse Bereavement Support, a registered UK charity, notes how men carry the propensity to compartmentalise, distract, or self-medicate, often through alcohol, work, porn, risk-taking, or other numbing behaviours.

When grief goes underground like this, it doesn’t disappear. It festers. It calcifies. And too often, it contributes to Australia’s disturbing suicide statistics. In 2023, men accounted for over 75% of suicide deaths in the country, many of them in the 40–60 age bracket. Not all of these are linked to grief, but unresolved emotional pain is a consistent thread.

The grief behind the curtain

Part of the difficulty is that not all grief is “public.” A man whose father dies receives condolences. A man who quietly loses his marriage, his career, his identity as a provider, or even a sense of future purpose, is often met with… silence.

This is disenfranchised grief, losses that aren’t always visible or acknowledged. They’re harder to name, harder to mourn. And yet they cut just as deeply. In midlife, many men confront the unsettling question: Is this it?

They may not say it aloud. But it’s there, in the middle-of-the-night insomnia, the growing disinterest in former passions, the tension that simmers under the surface, the silent chaos and despair. These are griefs of identity, relevance, and time. They deserve attention. And they demand better rituals.

Inventing new ways to mourn

There are signs of a quiet cultural shift. Men’s sheds, originally set up across the country to reduce social isolation, are evolving into informal spaces where grief, depression, and aging are openly discussed over tools and tea. A 90-year-old member of Oakey Men’s Shed up in Queensland, John Greenhalgh, shares that after his wife died, the Shed “gave me a will to live again.” Members regularly open up over coffee and tool-projects, even when grief is the undercurrent.

Bush retreats for men are becoming more popular, often blending physical endurance with emotional reflection and shared storytelling. Here in NSW, the Rock Bush Retreat is a venue used by groups such as Common Ground and Centre for Men Australia (CFMA) for rites-of-passage or grief-in-transition gatherings. Male-only groups convene in nature for reflection, storytelling, and emotional reconnection. For Dan Foster, CEO of the CFMA, this enables his vision that “every man in this country would have access to a group of mates that they can walk with shoulder to shoulder through life’s best and life’s worst.”

Even simple walking groups, where talking is optional but permitted, are creating space for connection and unforced vulnerability. The Man Walk is a nationwide grassroots initiative where men gather for a walk. No agenda, no coaching, no pressure. Talking is optional. What matters is presence. The walk is framed as a safe container for connection, support, and mental wellbeing in motion.

These aren’t rituals in the traditional sense. They’re not religious. They don’t involve candles or cassocks. But they serve the same function: giving shape to emotion, making grief visible, and allowing it to breathe.

Institutional support is lagging

Despite growing awareness, few workplaces offer meaningful grief leave beyond a few perfunctory days. Psychological services, while improving, are still underused by men, often because they’re accessed too late, or not accessed at all due to the stigma associated with Employee Assistance Programs.

There’s room for leadership here. Australian businesses could look to embed grief literacy into their wellbeing frameworks. Not just as a post-crisis intervention, but as a proactive skill. Just as we’ve normalised mental health through Aussie-grown programs like LetsTALK, we could train managers to better understand grief cycles and emotional flashpoints.

Policy alone won’t solve the problem. But if men knew their employers, and colleagues, were capable of holding space for their grief without judgment, they might actually use it.

Masculinity is not the enemy

None of this is an argument for abandoning strength, stoicism, or resilience. These qualities matter. They’re part of the masculine code for good reason. But they need balance.

Across cultures and centuries, traditional masculinity was not one-dimensional. It was expansive, layered, and deeply tied to community. Among Native American tribes, for example, men were not only hunters or warriors; they were also storytellers, peacekeepers, and spiritual guides. Elders played a vital role in preserving sacred rituals and oral histories, passing on wisdom with reverence and humility.

In Aboriginal Australian traditions, men are guardians of songlines, (complex, sacred maps of the land encoded in music and story), which are essential for spiritual and cultural continuity. Similarly, in Irish culture, some of the most beloved poets, balladeers, and storytellers were men, weaving grief, pride, longing, and joy into a heritage that shaped national identity. These men embodied a masculine ideal rooted not just in strength, but in service, artistry, and emotional depth.

In stark contrast, modern portrayals of masculinity, whether shaped by Hollywood action tropes or amplified by political rhetoric, often shrink this legacy to a caricature: the emotionally invulnerable lone wolf, the authoritarian alpha, the man whose power comes only from dominance or detachment.

This is a distortion, not an evolution. Rather than building on centuries of rich, multifaceted expressions of manhood, it reduces masculinity to rigidity, silence, and control.

Our ancestors knew better. They understood that true masculine strength comes not only from resilience, but also from vulnerability, connection, creativity, and care. To honour that legacy today means reclaiming a fuller, wiser image of what it means to be a man.

True resilience isn’t about suppression. It’s about integration. It’s about allowing grief to move through us, rather than calcify inside us. The Australian man doesn’t need to cry on cue or journal his way through heartbreak (though he can if he wants). What he needs is a language, a framework, and a few safe places to be real. With adequate time and space, grief can lead each of us to a heightened awareness of the fragility of life, and a newfound capacity for profound resilience. Grief prepares the way.

The privilege of love … and grief

We are not failing because we grieve. We are failing because we lack the tools to do it well. Grief is perhaps best viewed not as something to overcome but as a way of life, a constant companion intertwined with love. Grief is a reminder that we have the capacity to love, a reminder of the depths of that love, and is non-negotiable. We only grieve when we lose something we love.

For Australian men in midlife, grief is too often a solitary burden. It doesn’t have to be. With better rituals, old and new, we can change the script. We can make space for sorrow without shame. We can make space for small acts of kindness for those experiencing grief. We can make space for the brotherhood that helps counterbalance the darkness of grief.

And in doing so, perhaps we can build a culture where loss is not hidden but honoured.

It’s time to put down the brave face and pick up something more useful: connection, conversation, and the courage to feel. A precious form of honesty is found through the experience of grief and loss. We must find a way to reclaim it.

With love,

Stephen Keys